It is not for mortification (in the Catholic sense) that I write, on this Holy Thursday (and Good Friday as I post this), but to recall, and actually enjoy the memory of a great interesting trip to one of the “Holy Week places” in the Philippines. And that, of course, is Marinduque, the island province directly south of the isthmus of Quezon, where the province joins the Bikol Region, on the Batangas Bay. And you go there for the famous Moriones Festival.

The epic Ro-Ro ride to Marinduque island

If you’re a landlubber from Manila, you get to it by a rather long bus route from Cubao to Lucena, the major city in Quezon, roll on (in the same bus) to ferry for one-and-a-half hour ride from Dalahikan pier, and roll off at the island’s Mogpog port, and ride again for about 40 minutes, pass by the abandoned mountains of waste of the notorious Marcopper mine, and get down at the capital town of Boac. All this in little less than 12 hours, if it were not Holy Week. Because, if it were, the whole Philippine Christendom would be wanting to go there, not counting the droves of secular tourists, and there are not enough buses between Cubao and Lucena, ferries between Dalahikan and Mogpog. And because it is Holy Week (it was Good Friday last year when we made our trip, on National Artist’s Rio Alma’s tight schedule of soaking in Philippine places for a new poetry book), the bus and ferry ride would be nothing short of Dr. Shivago’s epic Siberian trip.

The citizens of Jerusalem in Boac, Marinduque

The citizens of Jerusalem in Boac, MarinduqueNow, the well-off and well-heeled Filipino would probably go on a pilgrimage to Jerusalem to join Franciscan monks on the Via Crucis, or if it were the time for it, attend the once-in-ten-years pageant at Oberammergau. The middle class would cool down in Baguio, or stand the heat to witness the Crucifixion and flagellation rituals in Pampanga or neighboring provinces, and the hoi polloi would go to the neighborhood Pabasa (reading-chanting of the Pasyon ng Hesukristong Mahal), do the Visita Iglesia, or gawk at a senaculo or Passion Play played by the local pious or neighborhood toughies. I am not well off (but I try conserve my heels), though closer to the hoi polloi, and was both lucky and surprised to be engaged once more to take photos for Rio’s book project. The other photographer friends begged out of the once-in-a-lifetime trip, and I dropped everything to join Rio, wife Lyn and son Agno, and witness Marinduque’s Moriones. And, I waited a year to blog this!

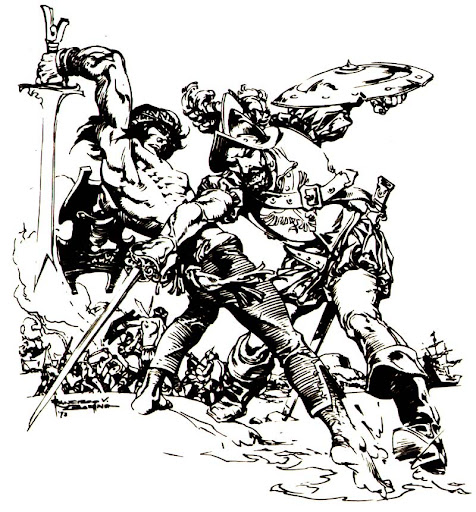

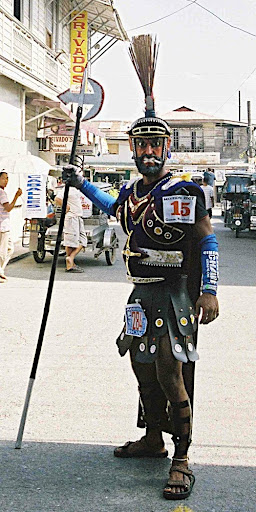

(left and down) A morion helmet from an Armor website; Magellan wearing a morion from F.V.Coching; Legazpi laid down his morion to toast Sikatuna with wine spiked with their blood, while his soldiers keep theirs on; an accurately marked Marinduque morion

The object after which the Festival is named is the 16th century helmet called morion. In the archetypal picture of the Spanish conquistador in the Filipino mind, it is the distinctive hat of the Kastila, a plumed or bare metal spherical head, and with it a leather (or is it metal?) cuirass on his chest, a saber or cutlass at the hip, and striped yellow-and-black bloomers and Robin Hood tights. Or, it is the barely visible plumed helmet that Legazpi lays down on the table before toasting Sikatuna in Juan Luna’s Pacto de Sangre. In my mind I like to think of F.V. Conching’s comic-book inking of Magellan making a lunge with his cutlass and Lapulapu evading with his ornate tabak before giving the final blow.

The Marinduque morion departs from the actual object and is both sacralized and profaned in the folk Passion pageant and festival. The Morion becomes a person with a mask depicting the face of the Roman centurion Longinus (Longhino). The Morion costume imitates and improvises on the Roman soldier’s. The mask’s countenance is the essence of viciousness, only to underline the conversion of the Roman soldier formerly blind in one eye, which is cured (is opened and sees the light) as he delivers the point of his spear on the Holy Side and blood gushes out and spatters his blind eye. Every Morion has a panata (sacred promise) to participate yearly in the festival until a divine favor is granted—a job, a baby for a childless couple, success in business, protection for a trip abroad, good luck before joining the diaspora.

Perhaps like the whole of Filipino culture and the post-colonial experience, the Moriones Festival is marked by color, pageantry, hybridization and bricolage. The individual Morion must prepare long beforehand his costume, or cobble up what’s available to him. The sophistication or manner of improvising the costume reflects the Morion’s status in life, and playing Longinus and wearing the mask in one blind eye is a special privilege. The mask itself, of varying designs and sometimes marked “Marinduque” on the visor, is preferably made of jackfruit wood and lasts a lifetime, many masks having been handed down through generations. Gasan town near Boac specializes in making the masks, and while other towns make their own masks (and stage their own Morion pageant), Gasan is the preferred source of the authentic and durable Morion mask.

Perhaps like the whole of Filipino culture and the post-colonial experience, the Moriones Festival is marked by color, pageantry, hybridization and bricolage. The individual Morion must prepare long beforehand his costume, or cobble up what’s available to him. The sophistication or manner of improvising the costume reflects the Morion’s status in life, and playing Longinus and wearing the mask in one blind eye is a special privilege. The mask itself, of varying designs and sometimes marked “Marinduque” on the visor, is preferably made of jackfruit wood and lasts a lifetime, many masks having been handed down through generations. Gasan town near Boac specializes in making the masks, and while other towns make their own masks (and stage their own Morion pageant), Gasan is the preferred source of the authentic and durable Morion mask.The Morion is both a fearful and comical figure. The thick beard on strong jaws, the bared teeth, the eyebrows coming together, and holes in the eyeballs (for the man behind the mask), both grotesque and ornamental, are all meant to scare, but does not exempt him from ridicule. We actually heard being chanted, as we saw our first Morion, the children chasing or running away from him as he threatened to chase them in turn: Morion bungi, may tae sa binti! (Gap-toothed Morion, you got shit on your leg!)

NEXT PAGE: A Morion Picture Book

poets'picturebook Issue 12 for posting March 31

No comments:

Post a Comment