but a whirl of art events continues despite or even because of what’s happening all around

1. Living on Loring

L

Last posting, about a serendipitous find in the Net of pictures by Maxim Popykin that reminded me of a trip to Russia twelve years ago, we also featured here the announcement for the art exhibit and event “Living on Loring.” Galleria Duemila is uniquely—or even typically—located. Just about next door to this patch of gentility and haven for the arts is a “huddled mass of shanties,” as Romina Diaz describes them. She is the photographer daughter of Silvana (nee Ancelloti) and Ramon Diaz who own the gallery. And she is the level-headed, socially-aware fine arts student who shuttles between Italy and Manila, who apparently cannot ignore the face of loneliness and squalor living nearby.

Around the old genteel enclave of Loring (where the residences of Manila’s old rich were located more or less before or just after the last War and until Edsa Extension cut through the area to connect to Roxas Boulevard), is the unignorable din of the city: the MRT commuter train station on the intersection of Taft Avenue and Edsa, and their obstreperous traffic—of vehicles, commuters, and God knows whatever else. Romina and siblings grew up among these, and she and the children of the other end of Loring Street would inevitably cross paths.

It is perhaps emblematic that Romina is called

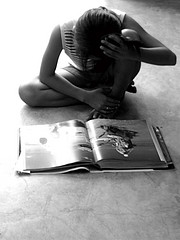

Ate (Big Sister) by the neighborhood girls, that she used to be walked by them to her bus stop or fetched by them at night during earlier school days. And that on the first night we got acquainted with her mother, on Lina Llaguno Ciani’s opening (the previous exhibit which ended February 29), as we lingered for last beers, they had to be excused because one of the kids of the neighborhood had got bitten by a dog and they had to take him to the hospital. And the days before as I prepared for a poetry reading for Lina’s show, I witnessed one of the sessions of the intensive photography workshop Romina conducted for the “Wild Cat” girls of Loring.

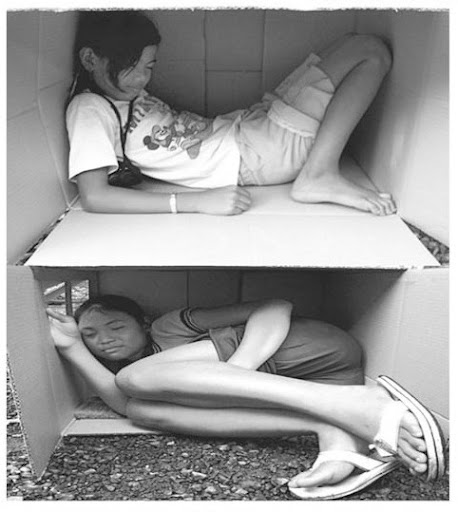

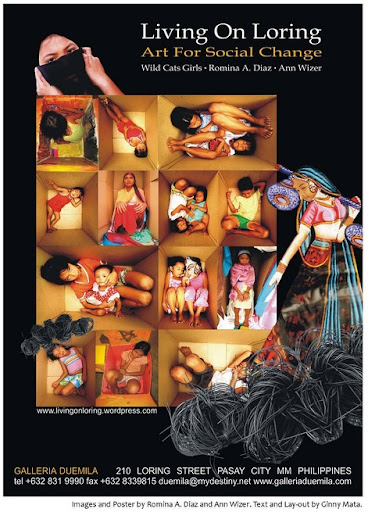

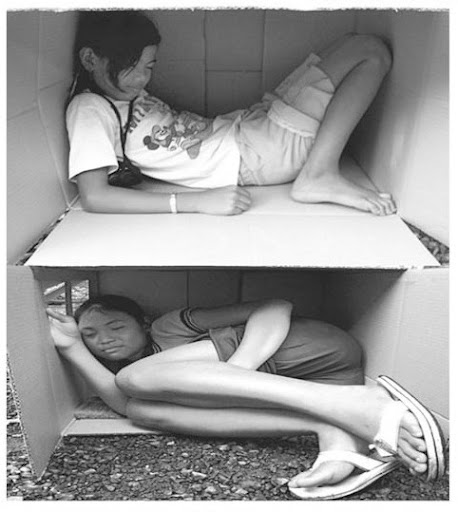

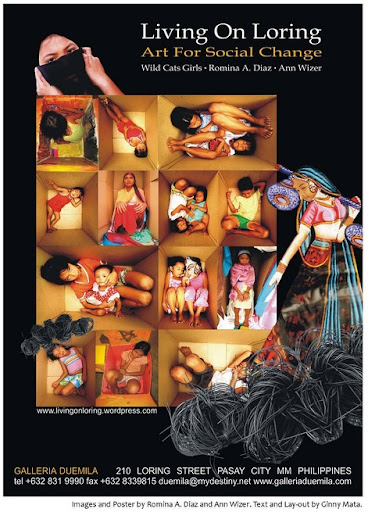

Thus “Living on Loring, Art for Social Change” came about. The photographic installations by the Wild Cat Girls of Loring Street, composed mainly of their photographs and portraits of the shanty life, were assembled together with LBC cartons and Balikbyan boxes. They also wrote journals and letters to their loved ones, or simply expressed their innermost thoughts on paper, all of which became their painted declarations on one part of the surrounding walls of the compound.

And to put the whole thing together, Romina joined hands with other artists, notably her collaborator Ann Wizer and curator Angel Velasco Shaw, the cross-cultural artist, writer, and activist. Velaco Shaw’s bigger project, “Trade Routes: Converging Cultures–Southeast Asia and Asia America,” had made “Living on Loring / Who’s Sita?” its kick-off venue, at the start of the International Women’s Month.

On hand to attend the affair, apart from most of the children of the neighborhood, were numerous artist friends of the Gallery, among them fellow Bikolanos, the abstract master Gus Albor, social-realist/expressionist Dante Perez, Maya Muñoz, film director Butch Perez (who I was surprised to find was a reader of this blog), and the great Tiny Nuyda, my idol since I've been following Filipino art, whom I met for the first time, and publisher Karina Bolasco, and social worker Hope Abella. Hope marveled at the “lightness” of the affair while taking on such serious issues as women and teenage problems, the ramifications of poverty on the young who, it seemed, found some relief, a possible way out, by means of self-expression. And this time it was through the art of photography that Romina shared with them, which in the end helped them confront themselves, and not least, their surroundings.

Romina Diaz

Romina DiazMyself, who’s back into the starving artist mode, freelancing after exiting from the comfort zone of a day job, was simply amazed at the whole thing—this seemingly impossible cohesion or collision between the realm of art, its patrons and consumers (the comparably rarefied), and the realm of the improvised box of discarded wood and galvanized iron and hard things, and the so called public art sprouting in between. It was both edifying and discomfiting, as I remarked to my companions half facetiosusly, that it felt guilty to be bringing a full wine glass into the territory of the fish ball. Eventually, when I asked for a refill at the bar inside the compound, I was relieved to be given a cup of Styrofoam.

“Living on Loring” opened on March 8 and runs for the whole month. It was a “wild,” exuberant carnival afternoon, a street party of deep-fried fish balls, corn-on-the-cob, banana cue, ice cream, poetry reading by Romina’s friends, the group Romancing Venus, composed of my friends Ginny Mata (host), Annabel Bosch, Kookie Tuason and Karen Kunawicz. There was a series storytelling by various groups that was evidently enjoyed by the kids, the last being hosted by Kuya Bodjie (Pascua) of

Batibot fame, and of course music by the Bahaghari Kalidrum and other performers.

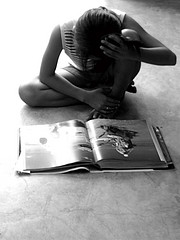

CAPTIONS & CREDITS from top: Photos 1-3, Loring Street & kids, girls in their boxes, reading, courtesy of the Living on Loring blog at WordPress; the invitation/poster; one of the photo-and-Balikbayan box installations; Romina Diaz reading her poetry at MagNet, by Ginny Mata; the installation art pieces.❜From My Shelf:

CAPTIONS & CREDITS from top: Photos 1-3, Loring Street & kids, girls in their boxes, reading, courtesy of the Living on Loring blog at WordPress; the invitation/poster; one of the photo-and-Balikbayan box installations; Romina Diaz reading her poetry at MagNet, by Ginny Mata; the installation art pieces.❜From My Shelf:Children of the Snarl

Streetwise at starfall they come,

Taunting the clumsy behemoths of the rush-hour,

The Children of the Snarl, unstartled

At the demented hunger of the highway,

Weaving a dance among eyes and fangs

Of myriad metal, prompted by their own hungers.

Merchants of poverty, dodgers of death,

They cheat mad chance in the flash of chrome,

In the glint of the fume-choked sun

Caught on the grime of the windshield glass,

In the storm-sunset on the fender-shine, offering

Flowers, appeasements for our own stale airs.

Our vision hurtles forward at morning

And dusk, borne by wheels tearing at space.

It hurtles between our faces in jeeps

Where we avoid each other’s gaze, somnambulant

Or asleep, with our sorrows and hurryings

Hidden, dressed and made up in haste.

There is no pause in the eyes that pursue

Their own appeasements. They peer at us,

We roll up our windows in vague defense,

Or concede buying a garland for our own icons

And talismans. Or choose a lottery ticket

For our chase of Ultimate Chance.

What link of flowers and lottery tickets

Joins us across the chasms of our classes?

What mindless mirth, hunger of eyes, insane dance

Of peddling small vices and poverty’s sweets

In the traffic of our haste convey us across

Craters in the asphalt, fissures in the concrete?

The lights time the rhythms of our chase.

The lurch and the wheel-skid summon their swarm

And us, Children of the Snarl: Slap of slippered

Feet, gnash of wheels worn smooth by pavements

Worn smooth by wheels, fume-storm in the crepuscular

Swelter of crushed petals and burning rubber.

And the rain season devours us, the headlights

Blind us: grit in the metal gutter, leaf-shard and

Insect-wing on the windscreen, stale air and perfume

From the aerosol spray. As dust, dirt and debris

And the day’s wrappers sail downstream, in the watery

Iridescences of the monsoon in the ditches.

Marne L. Kilatesfrom Children of the Snarl & Other Poems

Aklat Peskador, Manila (1986)